Quite a controversial idea probably, but I really believe it is true. This text is from my newsletter, to which you can subscribe using the yellow form on the right. The next newsletter is due on Saturday.

Lasker’s Psychology

I will start immediately with the shocker – there wasn’t any.

As many books have often repeated, I’ll paraphrase here, Lasker played the opening in a dubious manner in order to lure the opponent into unfamiliar territory and then outplay them. Nothing can be further from the truth.

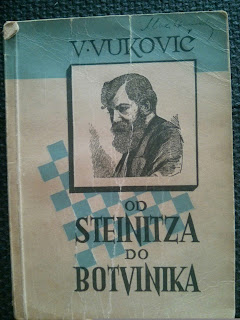

No strong player plays the opening dubiously on purpose. The fact that Lasker often ended up in dubious positions after the opening doesn’t mean that he intended it. As I have already written about this, and I advise you to read the part on Vukovic’s books for better understanding, I will just say that like anybody else he preferred to have a good position after the opening.

If there was any psychology in Lasker’s play, it was almost entirely his own. He didn’t care about the opponent so much. He was primarily concerned with his own safety.

Don’t let this confuse you. Popular literature leads you to believe that Lasker was the risk-taker, the gambler, the great fighter. Yes, he could be all these things once the game was under way, but before the game he was very cautious and often insecure. I would like to discuss two very famous games of his to demonstrate my point. In both he used the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez.

The first one is the first game of the match with Tarrasch in 1908. Here’s the game without comments.

We know that Tarrasch was a fierce critic of Lasker and often publicly stated that he wasn’t a worthy World Champion. They finally met in a match in 1908. It is not widely known, but before the first game Lasker was nervous and this showed in his comment to his brother. I don’t recall the exact words, but he said something along the lines, if I play the Exchange Variation, how can I possibly lose?

Note that he was primarily seeking a safe haven, he wanted to avoid losing in the first place!

The fact that he won shows that once the game started Lasker was just playing chess, trying to find the best moves. If an opportunity presented itself he would grab it and win the game, even if before it he was content with a draw. The game with Tarrasch was around equal most of the time, but Tarrasch erred and Lasker took his chance.

The second game is even more famous. In St. Petersburg in 1914 Capablanca was having a dream tournament. He was leading comfortably and playing excellent chess. He won the preliminary tournament with 8/10, a full point and a half ahead of Lasker and Tarrasch. These points counted toward the final standings and in the final he continued to play well. So what chances did Lasker have when they met in Round 7 in the final? He was trailing by a full point and he was playing a dangerous young opponent against whom he suffered for 100 moves in Round 2 of the final and who was openly intent on claiming his title.

Losing that game would have been a disaster for Lasker in the eyes of the public. Not winning the tournament and coming second behind the Cuban genius, much less so. How does then Lasker approach the game? No experiments, keep it safe and play the trusted Exchange Variation!

Just like in the game with Tarrasch, once the game started and he was safe out of the opening, knowing that he cannot possibly lose from that position, he started playing chess. And he outplayed Capablanca, who was probably somewhat confused: he became more relaxed after the innocuous opening choice but also concerned about what Lasker was trying to achieve.

These two games were the most striking examples I found of Lasker’s psychology. I was very surprised that even Kasparov, in his Predecessors book, fell for this myth of “Lasker the Psychologist” who played the Exchange Variation in the Ruy Lopez for a win.

“Lasker was a great man,” Capablanca said on more that one occasion. And great men are often misunderstood.