With all the players deeply immersed in preparation for the most important tournament of the year, and with Wijk and Gibraltar behind us, it is time to take a look at each player’s chances and prospects.

Of the 8 players only Ding Liren and Grischuk didn’t play anything in the new year. So let’s start with them.

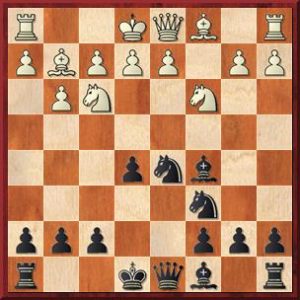

I am very much looking forward to Alexander Grischuk’s participation. He is one of the deepest and most original thinkers, especially in the openings. I will only mention two of his latest ideas that had a big impact on modern theory – one is the move …Bc5 in the English Opening after 1 c4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 g3 d5 5 cd Nd5 6 Bg2:

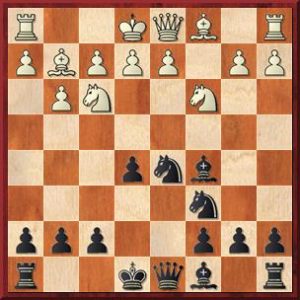

and the other, again in the English, and as early as move 2 (!) 1 c4 e5 2 d3, which he used to beat Anand in 2015. He also expressed his desire for the latter to be called by his name – after all, you don’t get to invent new ways as early as move 2 nowadays! I am curious what he will come up with in the openings this time. With White, he mixed the theoretical approach of going for the main lines with the non-theoretical (London System, Reti etc.). It is likely that he (like everybody else!) will tailor his approach to every opponent so we may see again a mixture of both. With Black against 1 e4, apart from the inevitable Berlin when wanting to play safe, he will undoubtedly come up with something else. In the last few years he was successful with the Sveshnikov Sicilian, but his latest Sicilian games have been in the Taimanov with transpositions to the Scheveningen. Against 1 d4 he has been experimenting lately, but the Grunfeld, an integral part of his repertoire since the Candidates matches in 2011, is definitely a possibility. All of these choices (and this applies for every player) will depend on his strategy for the tournament and also on the people he will work with (his decision to play the Grunfeld in 2011 was a result of him having Peter Svidler as a second). Apart from his opening originality, Grischuk is a player who is notorious for his time-troubles and this will both add to the excitement and harm his chances. Even though I am a big fan of Grischuk, I don’t see him winning the tournament, mostly because of his time-troubles. In order to stand a chance he will need to be in the form of his life, like in the Petrosian Memorial in 2014 which he won with 5.5/7 and crossed 2800. Let’s see if he manages – if he does, I for one won’t complain!

Ding Liren is the biggest mystery to me from all the 8 participants. A player with fantastic technique, excellent opening preparation and quite a resilient nervous system – his last round wins in the Sharjah Grand Prix over Aronian and in the Moscow Grand Prix over Gelfand were major factors in his qualification for the Candidates. On the other hand, he lost matches to So and Grischuk in 2016and Giri in 2017, so perhaps he needs to work to improve in situations with prolongued tension. He will have all the resources of China to aid him in his preparations. His opening preparation seems to be more limited than that of the others, his mainstay with Black is the Marshall against 1 e4 and the Semi-Slav with the Nimzo against 1 d4, while with White he is mostly a 1 d4 player. It can be expected that he will expand or change his openings, though I don’t expect him to change his manner of play. But only with great technique it will be impossible to win games in this field and for now I cannot see what can that extra spark be that will help him introduce something novel and give him a playing edge in the games. I don’t see him winning the tournament, but I do expect to have a better understanding of Ding Liren as a player.

All the other players had some practice in January so there is fresh information about them to be analysed.

One of my favourite players on the circuit is Vladimir Kramnik. Big Vlad had a very exciting Wijk, winning 6 games, more than anyone else, but also losing 2. Kramnik will undoubtedly come with fantastic preparation and I can only guess what novel concepts he will introduce. The only thing I think he will keep is the Berlin against 1e4. Against 1 d4 I think he will introduce new ideas within the already well-established openings in his repertoire as I don’t see him taking up the Grunfeld! I am more interested to see what he will do with White. He has been a proponent of the non-theoretical approach, like starting with 1 Nf3 and doing a double-fianchetto, and even though he still analyses these “offbeat” lines deeply, I am not sure this is the way to go in every game of the tournament. So I expect to see him mix it up, after all he has amassed such a big amount of opening analysis over the years! But Kramnik’s problems won’t be the openings, it will be his ambition. With Carlsen’s emergence and his insistence on playing until the end and looking for the tiniest chances, Kramnik successfully adapted and adopted this approach himself, becoming one of the most uncompromising players. His infinite belief in his abilities that he can beat anybody is perhaps natural for somebody who has been a World Champion and beaten Kasparov, but there is only one problem with it – he cannot keep that level of play, concentration and determination in every single game. There are too many ups and downs in his play and Wijk was an excellent example – he had two very bad games, the ones he lost to Giri and Karjakin and he had a few (just) bad games, the ones he didn’t win against Jones and Hou Yifan and the last round game he won against Adhiban (from a losing position). These are 5 games out of 13! In his desire to win he also made mistakes and dubious sacrifices in his games with Matlakov and So. With these two it is half the tournament! This kind of instability will not go unpunished in Berlin. I think that the Big Vlad of old, the stable and solid player who dethroned Kasparov would have more chances. But can he change his approach and adapt after years of “living dangerously”? If anybody can, it is Kramnik. But I am not entirely sure that he will see the need for it. And therein lies the core issue that will impede his chances of winning. This time his over-confidence and ambition will work against him. As much as I would like to see him win the tournament, I am afraid I have to say that he won’t. Though I can still hope…

Shakhriyar Mamedyarov had a wonderful year. His rise to the number 2 in the world with an impressive 2814 on the February list speaks for itself. Shakh has always been a very dynamic and aggressive player and while that gave him irresistible force, he was always susceptible to instability. This instability wasn’t only in his chess, it was also a psychological factor, when he couldn’t bring himself to defend for long periods and be resilient. But these things changed with certain important developments in his personal life. He got married (for a second time), quit alcohol and started playing “boring chess” (in his own words). These events brought Shakh what he needed most – stability. Now he is a much more complete player who won’t always go for a win at all costs. He has kept his aggression but this time it is a controlled one. He is also more relaxed and doesn’t consider the Candidates as a “must-win” tournament. This approach should alleviate the tension that will undoubtedly be felt by all participants. While the openings were never his main strength, he has introduced some novelties in his repertoire, like the Ragozin Defence with Black (in which he beat Svidler in 21 moves) and the Catalan with White. He also successfully used the element of surprise in his game with So, using the Nimzowitch Variation in the Sicilian (1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nf6) daring So enter wild complications in the main line. So, being unprepared for this, understandably declined and Mamaedyarov didn’t have problems to draw. Whereas Mamedyarov quickly fell out of contention in the previous Candidates tournament he played in 2014 due to instability at the start (he started with 0.5/3), the new Mamedyarov will not repeat the same mistake. If he can keep the same form as in Wijk, coupled with good preparation and wisely using the element of surprise Mamedyarov will be in serious contention. I still don’t think he will win, but it will be exciting to see him add another dimension to the tournament.

Wesley So on the other hand is an epitomy of stability. And stability will be a very important factor in Berlin. His tournament will depend on whether he manages to win a game or two. If he does he may as well win the tournament, but if he gets stuck and starts making draws he can easily replicate Giri’s 14 draws from Moscow 2016. The Candidates tournaments in 2013, 2014 and 2016 were all won with a result of +3 (8.5/14). Such “dense” tournaments work well for players who don’t win (and lose) a lot of games so even though being a newcomer in the field (all the others apart from Ding Liren have already played in a Candidates tournament) Wesley So shouldn’t find it any different from the usual tournaments he plays. In Wijk he introduced small changes to his repertoire: with Black he changed the line in the Catalan (instead of the main line he went for 4…dc 5 Bg2 Nc6 against Matlakov, though he did revert back to the main line against Kramnik) and surprised Anand with the Open Spanish while with White he tried the sideline 1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 g6 3 Nbd2 against Svidler in an attempt to avoid the Grunfeld. He is usually excellent in the opening and he will introduce some adjustments to his well-established repertoire. I expect him to be the same player as before – solid and not taking many risks. Can he win it? It is possible.

Sergey Karjakin had a relatively successful Wijk, winning two games, against Kramnik and Caruana, and drawing the rest. This was his first decent result in classical chess ever since the Sinquefield Cup last year where he scored 5/9, another decent result. His other results were far from decent, to put it mildly, but Karjakin’s focus since the match with Carlsen has been on promoting himself and milking out the maximum of his status and not on playing good chess. The result in Wijk may play a trick on Karjakin if he thinks that all is well because he managed to beat two of his competitors in Berlin. The main danger lies if he thinks that after a year of mediocrity he can rise to the occasion and perform at his best in Berlin. I would like to draw a parallel here. When preparing for his match with Spassky in 1972, after carefully analysing his games Fischer came to the conclusion that the level of Spassky’s play in the last year had deteriorated and he was now a weaker player than before. After the match Fischer said that Spassky played as he expected he would, i.e. on his lower level leading to the match. What I’m trying to say is that it is next to impossible for a player to drastically improve and raise his level after a prolongued period of mediocrity. Even though Karjakin will prepare very seriously I don’t see him as a candidate to win the tournament. His honeymoon period, which started with his win in the Moscow Candidates in 2016, will end in Berlin and he will have nowhere to hide – then we will see the true character of Sergey Karjakin. If he manages to get back to his best and return to the fight for the top places in the tournaments he is playing in or continues to freeload and just be one of the many.

Fabiano Caruana had a nightmare in Wijk. Losing 4 games and winning only 1 (in which he was also losing) is not something we expect of a player of Caruana’s caliber. This is even more surprising as it comes only a few weeks after his triumph in the London Classic in December. How will this bad result affect his play in Berlin? I don’t think it will. After suffering a serious setback the intelligent player will draw very important conclusions from it and will adjust accordingly not to repeat the same mistakes again. Additionally, after a catastrophe like Caruana’s Wijk, a player is more likely to be more careful in his next tournaments. I see this as a very positive development for Caruana’s chances in Berlin because, as I noted above, stability will be key in winning the tournament. And extra care can only be welcome. There is also a historical parallel to Caruana’s situation. In 2008, a month before his match with Kramnik in Bonn, Anand played a very bad tournament in Bilbao, finishing last with a -2 score on 4/10. And we all know how he played in Bonn. To conclude, I don’t think Caruana’s disaster in Wijk will affect his chances. What may affect them though, is his lingering problem with realisation of an advantage. In 2016 in Moscow he ruined his chances of winning the tournament by failing to win from winning positions in Rounds 11 (against Topalov) and 13 (against Svidler). He also had problems with this aspect last year, but surely he must have worked on this very hard and will pay special attention to it in his preparations. Speaking of openings, last year Caruana introduced the Queen’s Gambit Accepted and the Petroff Defence to his repertoire. This is an obvious attempt to be more solid with Black and the results have been pretty good so far, even though he suffered in a few endgames in the QGA (the line with 7 dc) and lost to Anand in the Petroff in Wijk. But he also introduced the Taimanov Sicilian in which he won an important game against Karjakin in London. This shows that he has flexibility with Black and can adapt his choices based on the situation. With White, even though primarily a 1 e4 player, he has also been experimenting with 1 c4, 1d4 with then either taking the route of normal theory or playing an odd London System. Caruana is stable psychologically, but has a more incisive style than So. Can he win it? Yes.

Levon Aronian was another player, beside Mamedyarov, to have a wonderful 2017. Coming out of the shadows after a lousy period he had excellent results and firmly re-established himself as a formidable force. He played in Gibraltar instead of Wijk, but he needed no less grit to win an open than it is required to win a Wijk. In 2017 Aronian’s main strength turned out to be his psychological resilience, something that was severely lacking in his previous decisive moments, particularly notable in the Candidates of 2013, 2014 and 2016. Aronian qualified for Berlin by winning the World Cup, the only person to achieve the feat two times. In a tournament when practically every game is a decisive one Aronian’s new-found inner strength carried him all the way to the finish line. Aronian is the only player to have played in all the Candidates tournaments since 2013, but this time it will be different for him. Previously he always started well only to spoil it later on as the tension was rising. With the recent experience from the World Cup he will know how to play in such circumstances. While the ghosts from the past will come back to haunt him, this time he seems better equipped to deal with them. Aronian’s repertoire is limited, especially with Black, when he sticks to the Berlin and the Marshall against 1 e4 and the Nimzo/Slav/QGD complex against 1 d4. He varies more with White, choosing between 1 d4 and 1c4. I don’t expect him to change his openings, but I do expect him to introduce new ideas in them. Aronian’s chess talent is one of the brightest and coupled with his newly found inner peace that brings him stability when it matters most, he is definitely one of the main contenders. Can he win it? Yes.

These are my thoughts on the most important tournament of 2018. Please share your thoughts in the comments.